As my fourth year (capstone) project, I was part of a team that developed organic semiconducting alpha detectors. The team did not prove that the devices can detect alpha particles, but showed a high degree of sensitivity to light, which is a common predictor of success at detecting radiation.

Typical radiation detectors are made from high purity Silicon or Germanium (HPGe), but have a couple drawbacks. The materials are brittle and inflexible, so any sensor must be made in it’s final shape. Additionally large detectors require weeks or even months of careful growth, with any impurities or imperfections reducing the efficiency of the detector. A major defect could mean scrapping the entire grown crystal and starting over, and these large detectors are highly expensive.

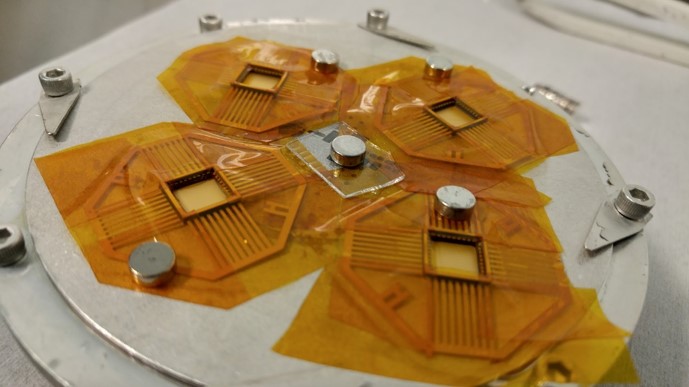

An array of Schottky Layout Detectors in Alq3

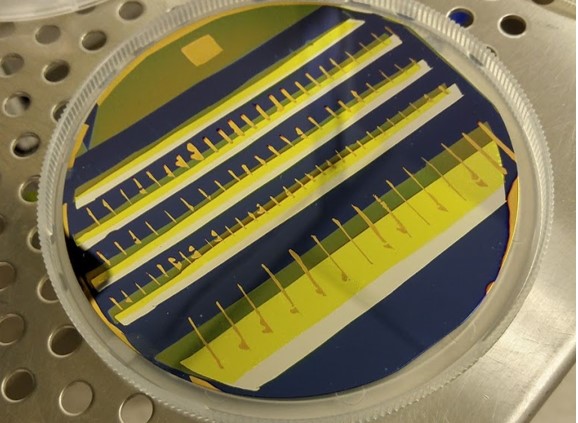

The organic materials we pursued are flexible, meaning we could build a detector and roll it into a tube, and place a source in the center, maximizing solid-angle coverage. Additionally the fabrication processes we use do not require careful crystal growth, and could be used to manufacture large detectors with ease.

My contribution to the project was primarily in modeling the radiation interaction with our detectors. For alpha interaction, this was primarily limited to using SRIM to determine a lower bound on the detector thickness, as alpha particles are easily stopped. Once we had determined that the lower bound for thickness would be constrained by the manufacturing process rather than alpha interaction, I moved on to modeling beta interaction.

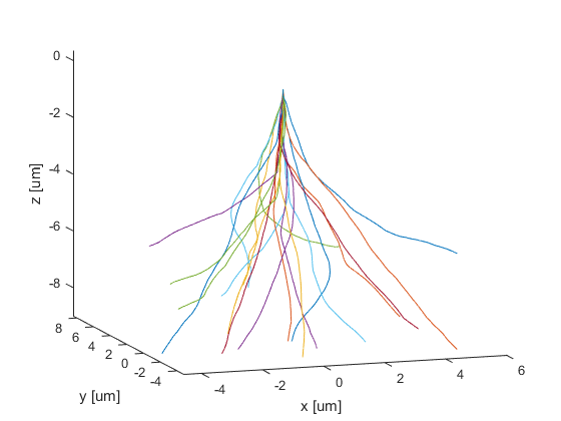

For detecting beta particles, the model is more important. Beta particles are difficult to stop, and if they’re traveling in a straight line, cover significant distance. Fortunately for the detector designers, beta particles don’t travel in a straight line in a detector. Instead they bounce and ricochet around within the material, with their overall path curving, turning, or even doubling back on itself.

This path is complicated to model due to the speeds and interactions involved. I implemented a monte-carlo simulation using the Bethe-Bloch equations at relativistic energies. The simulations builds a large number of potential paths through the material, and can the be summarized to extract bulk parameters. These parameters include effective stopping power, range, and straggle, and directly support the design process for any beta detectors.